How Singapore Strengthened Its Laws to Counter Terrorism Over The Years

To mitigate the continuing threat of terrorism, Singapore has been strengthening its laws throughout the years. Terrorism financing has been strongly prohibited and strict controls on the sale and possession of weapons was implemented. The said matter was addressed by Mr. Desmond Tan, Minister of State for Home Affairs, as published on the Straits Times. This arose from the current arrest of a 16-year-old self-radicalized Singaporean and the country’s plans against extremism and radicalisation.

The arrest of the said Protestant Christian youth took place in December, after he prepared detailed plans to attack Muslims at two mosques by using a machete.

Mr. Tan mentioned that the Terrorism Act (Suppression of Financing) has been updated after it was implemented in 2019. “Key changes included expanding the prohibition on financing terrorism activities to include terrorism training, and increasing penalties for failing to disclose information relating to terrorism financing to the authorities.”

Singapore Government also implements stringent controls on offensive weapons and firearms. The Arms and Explosive Act was replaced with the Guns, Explosives and Weapons Control Act. This law applies regardless on the mode of sale, whether via physical store or online platforms.

"The Government has publicly condemned overseas terrorist attacks. We are also fortunate to have the support of our religious leaders, who have been proactive in publicly condemning terror attacks and reminding their followers to stay calm and not react to expressions of extreme sentiments and acts of violence in the name of religion”,he said.

Dean Morados: I know my faith and I am Muslim

Last July 24, The Peacemakers’ Circle, an organization of Filipino people with diverse religions, spiritual expressions and indigenous traditions, hosted an online Interfaith Dialogue dubbed “The Call of My Faith. The Challenges I Face” which was attended by a number of Filipino peace advocates. One of the keynote speakers was Assoc. Prof. Pablito A. Baybado, Jr., PhD, the Associate Secretary General of Religions for Peace Asia, Executive Secretary of the FABC-Office of Education and Faith Formation, and member of Religious Educators Association of the Philippines and DAKATEO-Catholic Theological Society of the Philippines. Bong, as he is fondly called by friends in the interfaith community, is a Catholic Christian who holds a doctoral degree in Philosophy and is the Theology Program Lead of the Graduate School of the University of Santo Tomas (UST). He is dedicated to promoting peace and harmony among peoples of diverse religions, spiritual expressions, and indigenous traditions through various forms of dialogue.

Another keynote speaker was Dean Macrina A. Morados who is an Associate Professor and Dean of the Institute of Islamic Studies (IIS) at the University of the Philippines in Diliman. She has been serving the academe successfully in various leadership capacities but is best known and loved by The Peacemakers’ Circle Foundation, Inc. (TPCFI) for her unflagging support of its interfaith peacebuilding initiatives through the years. She has been helping TPCFI in the endeavor of bringing together student leaders of UPIIS and the nearby Ateneo de Manila University in initiatives that promote relationships of mutual respect and understanding between Muslim and Christian youths and creating safe spaces for dialogue and cooperation among them.

During the interfaith dialogue, Dean Morados shared a beautiful speech on the challenges that she faced as a Muslim and provided some insights on how to address these challenges. Below is the inspiring speech of Dean Morados:

Assalamu Alaikum . Peace be with you.

I was born in Jolo, Sulu and just before the war broke-out and the burning of Jolo in 1974, my parents decided to move to Davao del Sur. I was 6 years old at that time, so my childhood recollections would always bring back memories of my family living in non-Muslim community and having non-Muslim friends. The nearest mosque and Muslim community was like 20 minutes ride from our place.

We grew up questioning many things, like why can’t we eat pork? Our playmates enjoyed the lechon during barrio fiesta. Why can't we attend and join the Flores de mayo parade? My mother would tell us not join gatherings to venerate Virgin Mary because she is Sitti Maryam in Islam and should not be depicted in any form.

All the while, I understood later, my parents were facing big challenges in keeping our identity as a Muslim. They imparted to us basic rules of Islam – we learned the shahadah, the fatiha, the early fasting training. At age 10, we were trained to fast.

Despite having a different religion from our neighbors, I witnessed my parents’ very welcoming attitude towards our neighbors and sharing with them whatever we have. My father was a fisherman and he always set aside some fish for our neighbors. Our neighbors did the same to us, I remember during fiesta some neighbors gave us chicken assuring us it was free of any pork ingredient.

And my experience with Non-Muslim friends became even more personal to me when I entered the RVM convent in Sta. Cruz as a working student of Sister Sabina Brinan, RVM. I helped her in the RVM literacy program of the Badjaos in Sta. Cruz, Davao del Sur.

I finished my high school education with the help of the RVM sisters. I was the only Muslim allowed to stay in the convent. I was attracted to the very contemplative life of the Sisters and I told Sister Sabina I want to become a nun. She told me to understand Islam first. She challenged me to study my faith and come back to her if after learning Islam and I still want to become a nun.

After High School, I went to MSU General Santos City. I started searching for the deeper meaning of my faith. I got hold of the English translation of the Qur’an, attended Islamic seminars and read many books about Islam. Allah swt guided me to Islam with correct understanding of its teachings.

In 1993, I met the focolare movement and I felt it was like going back home to the convent, but that time I was so assured -- I know my faith and I am a Muslim. I felt more comfortable engaging with them. And it was there when I had that great moment of understanding why Allah swt allowed me to stay in the convent and fell in love with the nuns’ vocation, I realized Allah swt has a greater plan for me. In fact, many of my Muslim colleagues were so amazed of my very trusting and comfortable stance every time I am with Christian friends. All I know, my experience with the Sisters in the convent, with the focolare and now with the interfaith circles like our group and individual partners was not a coincidence but Allah swt has prepared me to face greater tasks in bringing Islam closer to the heart of my non-Muslims friends by sharing to them the friendly and tolerant Islam taught by the Qur’an and lived by the Prophet Muhammad swt.

At this point in time, the greatest challenge I faced as a Muslim is the proliferation of the ideology of violent extremism, for the past several years especially after 9/11 we see how people claiming to be Muslims hijacked the beautiful teachings of Islam. People use Islam to justify their violent actions contrary to the teachings of Islam. Have you remembered, during the Bombings in Boston, in Paris, in New Zealand, and for the local incident the bombing of the Cathedral in Jolo, in our silent moment we utter apologies to the victims because the world is made to believe that the culprit are Muslims. We all know that the culprit is the ignorance of the violent few and lack of understanding and appreciation of the Qur’an.

So how do I respond to this challenge? The only way is through education and reaching out to the most vulnerable sectors in the Muslim Ummah, that is women and the youth. I started my advocacy with women in jail since 2005, but the problem is recurring. We have to highlight the role of women in the community. They are the best educators and peace builders and teachers, beginning the early education of the children at home. This is one of the calls of my faith--to change the narratives of Islam.

One best example I can share to you the positive effect of educating our youth who happens to be MA students at the Institute. I am referring to the Reskyu team. Our students organized themselves and launched clean-up drive at Muslim compound. Recently, they spearheaded a three day celebration of Eid Adha in the community to foster unity of the tribes and to give the youth the chance to contribute to the Ummah.

The next pressing and most challenging concern that we face as Muslims is to combat if not lessen and eradicate the threat of COVID 19 in our community. Our faith has many things to offer to combat the surge of COVID 19. One is to abide by the teachings of the Prophet. Performing ablution, avoiding intoxications, segregation somehow a good social distancing strategy and final riba there is an acknowledgment social obligation – protecting people from dire poverty.

What would be our response to the needs of our fellow Muslims? We have to remind ourselves about the injunctions on Zakah and charity. And our experience last Ramadan affirmed that through dialogue in action our interfaith circles were able to show to our Muslim brothers and sisters our solidarity with the Muslims during the pandemic in the most special occasion of Ramadan.

Mustaqim Philippines admires the efforts of all Filipino peace advocates. May they continue to inspire others to tread the path towards peace.

What Drives a Person to Become a Violent Extremist?

There are several reasons why a person would choose the path of being a violent extremist. In the USAID’s published document in 2009 titled “Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism”, five main categories of motivations for individuals to join or support VE were pinpointed:

- Fairly circumscribed and specific political (especially territorial), economic and social grievances.

- Much broader ideological (especially religious) objectives.

- The search for economic gain.

- Motivations that relate to an individual’s personal background (e.g., the desire to avenge a loved one).

- Intimidation or coercion by peers or the community.

In the FBI’s article titled “Why do People Become Violent Extremists?”, seven major personal needs were mentioned namely power; achievement; affiliation; importance; purpose; morality; and excitement. If these needs remain unmet, it will most likely lead to radicalization and VE.

In the case of Southeast Asia, UNDP’s study titled “State of Violence: Government Responses to Violent Extremism in South-East Asia” argues that heavily securitized state responses to VE, exclusionary politics based on religious and ethnic identity, state action and inaction that reinforces hate speech and intolerance in society, and the use of violence against citizens are all ways governments can engender further violence.

In the Philippines, The NAP P/CVE clearly defines the push and pull factors to radicalization leading to VE. As defined in said document, push factors are the root causes such as poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, historical grievances, discrimination and political and/or economic marginalization while pull factors are the so-called “benefits” from an extremist organization that entice vulnerable individuals to join. These include the group’s ideology, strong bonds of brotherhood, reputation building, prospect of fame and glory, and other advantages gathered from socialization and belonging in a group. Additionally, the NAP P/CVE discussed that the identification of specific push and pull factors in a particular community or sector requires careful and detailed study which can be likened to a doctor assessing a patient’s condition prior to recommending treatment. Though doctor’s assessment is far from being infallible, the goal is to come up with the most appropriate intervention programs to address actual drivers and ultimately reduce vulnerability of sectors to VE.

Some other drivers of VE include the following:

- Political deprivation leading to hopelessness or a sense of powerlessness.

- Long festering political disputes.

- Lack of education and poverty.

- Ideological imperatives that may lead to extremism.

- Socio-economic inequities, unemployment, despair about the future.

- Corrupt and self-serving dominant elite.

- Foreign occupations.

- Sense of victimhood amongst Muslims.

- Resurgence of Islam phobia in Europe.

- Education and training in a narrow religious and cultural framework creates people with a narrow and bigoted worldview and breeds intolerance and extremism.

- Children who are exposed to violence at an early age tend to adopt violence as a way of life unless de-linked from early experiences (Child Soldiers of Africa and Pakistani Children who experienced war in Afghanistan alongside Taliban).

- The media regularly gives negative messages about people from minority groups/ people from other countries.

- Extremism groups usually target susceptible young people. These young people might be lonely, bored or “lost”.

- Extremist training for young people can be very ‘exciting’ and can provide strong friendships.

- Unemployed young adults sometimes feel that extremism gives them a purpose to earn and fulfill their basic economic needs.

- Young adults who did not achieve well at school sometimes use extremism as a way to feel that they are succeeding and henceforth important.

- Some extremist groups believe that they are following God’s instructions. As such, they do not understand that what they are doing is wrong.

- Family members sometimes encourage extremism.

- Extremist websites/ videos have a big impact and are hard to regulate.

- Social networking websites allow people all over the world to influence each other.

- Some citizens feel that they have been treated unfairly throughout life, and want someone to blame or punish.

- Some citizens who move to a different country find it hard to adapt to their new life. They look for someone to guide them and fall into the wrong hands.

- Violence is increasingly glamorized by the media.

- Teachers and police officers do not usually have enough training to recognize extremism or to deal with it.

Sectors that are Most Vulnerable to Violent Extremism

The Philippines’ National Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (NAP P/CVE) has laid down the 6 main sectors that are most susceptible to VE.

1.) Community – As stated in the NAP P/CVE, the presence of various drivers to extremism in the community such as marginalization, discrimination, inequality, structural problems make the community vulnerable to radicalization that leads to VE. Because of this, it is vital to identify these drivers that contribute to the openness of the community to VE.

In both Muslim and non-Muslim communities in the Philippines, the NAP P/CVE states radicalization can take place because of underdevelopment, poor governance, land problem, displacement, military and police abuses, and exclusion. Sharing these grievances against a perceived common enemy which is the state’s security forces, rebel fighters can easily associate with and be part of criminal gangs, private armies of local warlords, secessionist groups, communist terrorist groups, and other armed groups.

Therefore, while local terrorist groups (LTGs) are seen to be heavily focused in Mindanao, the dispersed terrorism-related attacks and other forms of violence persisting in various areas of Luzon and Visayas makes VE a national rather than just a Bangsamoro concern. This is also the reason why the Philippines has a stake in realizing a stable, secured, and developed Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

2.) Persons Deprived of Liberty with Terrorism-Related Cases (PDL with TRC) in Jails and Violent Extremist Offenders (VEOs) in Prisons - In 2015, the Penal Reform International Prisons discussed that penitentiaries could play a critical role in both triggering and reinforcing the radicalization process. The number of prisoners in prison for violent extremist and terrorist offenses is believed to be increasing globally. The treatment of these prisoners is a defining issue for prison services who must fulfill human rights obligations, ensure their rehabilitation and reintegration, and maintain the safety and security of all prisoners in their care. It was also commented that the terrorist group ISIS recruit prisoners to VE through promoting the idea that this will help to compensate or atone for their offending and the harm they may have done to their family. These prisoners succumb to VE because of the poor conditions in prisons, including overcrowding. The discussion centered on whether to disperse prisoners deemed to be at risk of radicalizing other prisoners within the general prison population or to hold them separately in concentrated units. Several participants from prison authorities emphasized that holding prisoners in isolation from others was damaging to physical and psychological health and well-being and likely to prevent rehabilitation. The lack of access to adequate health care as well as long periods in pre-trial detention can create a context in which radicalization can flourish and where the implementation of prevention programs is challenging to accomplish. How security forces deal with the investigation stage of proceedings can also be a driver for radicalization and reinforce a sense of grievance and victimhood. Policymakers must decide whether extremist offenders should be subject to regular rehabilitation and reintegration interventions or whether new programs are needed that are specifically tailored to their unique needs and challenges.

Jones (2016) discussed the situation in the two main correctional facilities in the Philippines: The New Bilibid Prison (NBP) and the Metro Manila District Jail (MMDJ). The NBP appeared to integrate terrorist inmates into the general prison population while the MMDJ segregated its terrorist inmates from the mainstream prisoners. The NBP’s environment includes overcrowding, where overstayers become the major problem. This is caused by an ineffectual judicial system that contributes to the development of prison gangs. The NBP prison population includes around 45 individuals who are known to be terrorist offenders due to their associations with proscribed terrorist groups. Terrorist inmates are given no particular classification and are not treated any differently to other prisoners. Over a period, fitting in with gang culture appears to become a primary objective for survival, and somehow, radicalizing other inmates becomes a secondary consideration. Pressures to conform to the prison environment and the demands of the various dominant social groups seem unavoidable. On the other hand, in the MMDJ, mainly in the Special Intensive Care Area – 1 (SICA – 1) building, there are four levels: lower floor -terrorist inmates; second floor -New People’s Army (NPA) inmates; third floor -Chinese drug traffickers; and the fourth floor -TB sufferers. There are about 250 suspected of being members of terrorist organizations. This detention facility also has a problem with overcrowding. In July 2014, a video appeared on the internet showing prisoners performing a bay’ah to al-Baghdadi from within SICA – 1 facility. In SICA – 1, there are signs of conversion to Islam of other inmates on the upper floors. In most cases, such modification is a healthy step for rehabilitation and minimizes the pains of imprisonment.

The NAP P/CVE discussed that empirical evidence shows how prisons can potentially serve as breeding grounds for radicalization and recruitment. The US detention center in Camp Bucca, Iraq is considered as instrumental in the forming of ISIS, where nine of its top members were incarcerated and given the time and space to deepen their extremist beliefs and radicalize other detainees. Indonesia is similarly hurdling the challenges of prison-based radicalization which persists due to overcrowding, co-location of hardened ideologues and ordinary inmates, and lack in number and capacity of prison staff to manage high-risk prisoners. With these problems and the lack of coordinated efforts between government agencies and non-government organizations, deradicalization programs fail to be effective. As a result, radicalized detainees continue to conduct terror acts when released as demonstrated by those who staged the Jakarta attack in 2016 after being radicalized by ideologues in an Indonesian prison.

This same set of problems also exist in the Philippines. Subsequently, it makes separation and distinct handling of high-risk PDL with TRC and VEOs from general inmate and prisoner populations as well as implementation of counter-radicalization, deradicalization, and aftercare programs doubly difficult. Such broad challenges in the country’s jail and prison systems are creating conditions for radicalization to occur and progress among the PDL or those awaiting and undergoing trial or awaiting final sentence, and the prisoners or those who are serving sentences.

3.) Religious Leaders - Across the globe and among different cultures and traditions, religion is being misused, in different degrees and forms, directly or indirectly, as motivation, reason, or justification for committing violence to advance a cause. The NAP P/CVE discussed Al-Qaeda and ISIS are the most infamous ones for capitalizing religion to have a wide range of influence in their radicalization activities, spanning from Middle East to Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines.

At the height of the Marawi City siege, some Muslim religious leaders were said to have an unsure stand or mixed feelings on the Maute Group. The danger that this posed arose from their unawareness of the radicalization happening within this group and this resulted in several violent extremist acts that they were helpless to act against.

As mentioned in the NAP P/CVE, the said ambivalence showed the vulnerability of the Muslim religious leaders to extremist influence due to the varying streams of Islamic schools of thought prevailing in the Philippines.

4.) Learning Institutions - Another vulnerable sector to VE identified by the NAP P/CVE are the different learning institutions such as schools, colleges, and universities; and the Madrasah. These educational centers may be exploited by violent extremists to influence and radicalize the minds of the children and the youth. On the other hand and more importantly, these institutions can also serve as venues to promote peace and prevent the spread and counter the influence of radical ideologies.

5.) Social Media Users - The NAP P/CVE discussed the internet has made being part of the global community easy. With its scope and ease of access, one can reach out to many people at once and all kinds of information can be sent and received regardless of geographical boundaries. Put into the wrong hands, this technology can be used as an engine for the spread of extremist ideas.

Therefore, online radicalization that leads to VE happens in the realm of cyberspace as individuals, who are otherwise hard to reach through traditional means, become exposed to a belief system or ideology that encourages the use of violence to realize political, social, or religious goals. Through social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube and other websites facilitating exchanges, extremists can interact with individuals anywhere in the world and build a common worldview where radical ideas and violence are normalized and even glorified.

6.) OFWs and Overseas Scholars - As stated in the NAP P/CVE, the heavy concentration of Filipinos living and working in Western Asia or the Middle East makes them a target for recruitment or direct attacks by extremist groups. Thus, protecting the Filipinos overseas from radicalization and VE is a pressing security challenge for the Philippine government. Meanwhile, efforts to partner with countries concerned are continuously being done as part of the country’s counter-terrorism efforts. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for instance, has recognized this problem and called on the Muslim scholars in the Philippines who were mostly educated in the Middle East and Africa and are operating Madaris, mosques, and other religious organizations to help in the prevention and countering of VE.

Further, religious scholars trained abroad are also exposed to radical teachings of some of the sponsoring organizations and religious and educational institutions that finance their studies. Hence, programs to raise their awareness about radicalization, strengthen the monitoring of sponsoring organizations, and forge partnerships with countries concerned must be pursued to reduce the vulnerability of OFWs and students abroad to radicalization that leads to VE.

References:

- Penal Reform International. (2015). Proceedings of International Expert Roundtable, Amman, Jordan. 1 -11.

- Jones, Clark. (2018). "Are Prisons Really Schools for Terrorism?" Lecture, School of Regulation and Global Governance, Australia, Australian National University.

- McCoy, Terrence, 4 Nov 2014, “Camp Bucca: The US prison that became the birthplace of Isis”, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/camp-bucca-the-us-prison-that-became-the-birthplace-of-isis- 9838905.html

- Moir, Nathaniel, 2017, "ISIL Radicalization, Recruitment, and Social Media Operations in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines," PRISM, Vol. 7, No. 1, published by the Center For Complex Operations, National Defense University.

- Karmini, Niniek, 9 Feb 2018, “Study: Extremists still flourishing in Indonesia’s prisons”, https://www.apnews.com/b1d8e7bf7c9f49448410f6ac0b7919ee

- Mandaville, P. & Nozell, M., August 2017, “Engaging Religion and Religious Actors in Countering Violent Extremism”, United States Institute of Peace Special Report.

- Carmela Fonbuena, Philippines Muslims called to jihad vs extremists. September 9, 2017 available at https://www.rappler.com/nation/181608-jihad-extremism-philippines

- Community Oriented Policing Services, U. D. (2014). Online Radicalization to Violent Extremism. Washington, DC, United States of America

- Peter Chalk, The Islamic State in the Philippines: A Looming Shadow in Southeast Asia, March 2016, Volume 9, Issue3, at https://ctc.usma.edu/the-islamic-state-in-the-philippines-a-looming-shadow-in-southeast-asia/

- Moh Saaduddin, Muslim Scholars tapped to fight extremism, The Manila Times, February 25, 2018 at ww.manilatimes.net/muslim-scholarstapped-

fight-extremism/382538/

What is Violent Extremism?

The Counter-Terrorism Module of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) provided several working definitions for the term Violent Extremism (VE). In Australia, VE is defined as “the beliefs and actions of people who support or use violence to achieve ideological, religious or political goals. This includes terrorism and other forms of politically motivated and communal violence." In the USA, the FBI defines VE as the "encouraging, condoning, justifying, or supporting the commission of a violent act to achieve political, ideological, religious, social, or economic goals". Meantime, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) defines violent extremist activities as the "advocating, engaging in, preparing, or otherwise supporting ideologically motivated or justified violence to further social, economic or political objectives". In Canada, VE is where an offence is "primarily motivated by extreme political, religious or ideological views". Some definitions explicitly note that radical views are by no means a problem in themselves, but that they become a threat to national security when such views are put into violent action.

In tackling VE, Southeast Asia proves to be the most experienced and in a much better position compared to most countries. As defined in the Philippines’ National Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (NAP P/CVE), VE is a belief system that drives individuals or groups to commit violent acts. This belief stems out of a context of repression, poverty and other so-called “push factors” made attractive by “pull factors” such as money, power, sense of purpose desired by the recruits, and charismatic VE leaders. The aim of VE is the furtherance of causes that are ideological, religious, political, social and/or economic in nature. It fosters hatred that may lead to intercommunity violence. According to the document published by the United Nations Development Plan (UNDP) in 2020 titled “State of Violence: Government Responses to Violent Extremism in South-East Asia”, VE occurs when a tightly defined group feels threatened by the world outside and decides to use violence against members of an out-group. These groups may be defined by political views, ethnicity, religious beliefs, or a combination of these characteristics. Groups are driven primarily by their own political experiences even if they are inspired by global movements or outside leaders. The UNDP states that South-East Asia has seen various violent groups wax and wane over the years.

Other references:

- Parliament of Australia (2015). " Australian Government measures to counter violent extremism: a quick guide."

- Public Safety Canada (2009). " Assessing the Risk of Violent Extremists." Research Summary, vol. 14, no. 4.

- USAID (2011). " The Development Response to Violent Extremism and Insurgency: Putting Principles Into Practice." USAID Policy, September 2011. P. 2.

What are the Determinants of Extremism?

Extremism, a disease of our times, has spread its tentacles all around. Of its many defining determinants; at least three are noteworthy.

One, the extremism that those in power exhibit. They go in with tanks and bombs where patient force backed diplomacy can work, seek to destroy what requires careful reconstruction, advance division and hate where understanding and bridging of differences is needed, and abandon the path of justice and fair play for pure partisanship. All this naturally promotes deadly and debilitating extremism.

Two, in the absence of a credible and participatory system of politics and a reliable justice system, political groups often frame their concerns and solutions in an extremist manner. When a non-credible political system leads to the unconstitutional imposition of the rule of a specific elite, party, ethnicity or institution over the ‘rest’ the response of the rest is often cast in extreme ethnic, religious, anti-elite or anti-institution character. Hence through exaggeration of their legitimate concerns, they construct a victimhood scenario. In countries where credible political and legal systems do not exist, many would buy into victimhood framing. The causes of discontent may be numerous. They could be political, cultural, sociological, economic and moral.(Examples are East Pakistan, Kashmiris, Palestinians, Naxalites or even Balochistan).

Three, perpetual discontent breeds frustration, irrationality and desperation and a mind that will almost effortlessly take to extremism, like fish to water. They have virtually no stake in the dominant socio-political and cultural milieu. Morally too they find it repugnant. The milieu is often framed as the ‘evil’. From this repugnance they often derive justification to destroy the other. They opt for the anarchistic, nihilistic or messianic route to worldly and heavenly salvation.

Let Us Define Extemism

Literally, extremism means being situated at the farthest possible point from the center. Figuratively, it indicates a similar remoteness in religion and thought, as well as behavior. Extremism is a term used to describe the actions or ideologies of individuals or groups outside the perceived political center of a society. Extremists violate “common moral standards” and, in democratic societies, branded extremists are individuals or groups who advocate that democracy should be replaced with some kind of an authoritarian regime.

In a simpler sense, extremism can be seen in a person’s unwillingness to discuss and take into consideration other people’s views. More often than not, extremists tend to have higher levels of emotion, usually leaning towards anger and discontent. Also, extremists tend to isolate themselves from society and work almost secretly in almost all their dealings. It is important to note that all of these characteristics do not automatically equate to an extremist being a dangerous person. We can only say that an extremist is threatening when his ideology calls for the use of violence.

Canadian Muslim Rights group and Fighting Islamophobia

TRT World, a Turkish public broadcaster news channel reported that Canada’s National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM) released a report which includes several recommendations on how to stop Islamophobia in Canada.

The NCCM, issued 61 recommendations calling for action at the federal, provincial and municipal levels, stating that more Muslims have been killed in hate attacks in Canada than any other G7 country in the last five years.

To note, in 2017, a deadly mass shooting at a mosque in Quebec City left six Muslim worshippers dead. More recently, a terror attack on June 8 killed four members of a Muslim family in London, Ontario. The incident sparked renewed calls for authorities to deal with systemic anti-Muslim bigotry.

The Edmonton area has seen a number of hate-motivated assaults since December 2021, most of which have involved complainants that have been Muslim, Black or both. Mosques have also been vandalised and prowled by far-right groups.

“While we have heard many words from politicians condemning Islamophobia and standing in solidarity with Muslims in Canada, action to tackle Islamophobia has been slow and piecemeal,” the NCCM said in the report.

“We cannot stand by and see any more lives lost. Islamophobia is lethal and we need to see action now,” it said.

Among the recommendations are calls for a federal anti-Islamophobia strategy by the end of the year, which includes a clear definition of Islamophobia, funding for anti-Islamophobia research and public education campaigns.

It included designating a national support fund for survivors of hate-motivated crimes, which would cover expenses incurred by survivors, such as medical and/or mental health treatments; preventing profiling and mass surveillance of Muslim communities through Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) reforms; and anti-bias training for government officers and judges.

NCCM also recommended an investigative study into the failure of national security authorities to deal with white supremacist groups in Canada.

Among criminal code amendments recommended were the introduction of provisions around hate-motivated assault, murder and threats.

Media representation by incentivising production of Muslim stories through funding in the Canada Media Fund and National Film Board, was highlighted as well.

At the municipal level, the group advocates for bylaws that give authorities the power to fine people who engage in street harassment.

It also called for investment in “celebrating the history of local Canadian Muslims” through events and spaces where their accomplishments can publicly counter negative stereotypes and caricatures.

The NCCM report comes ahead of a national summit on Islamophobia set to take place on July 22, a day after a national summit on anti-semitism.

Mustaqim Philippines hopes to see all of these recommendations in action not only in Canada but also all across the world as we also condemn, in the strongest of terms, all forms of violence against people from all walks of life.

Source: https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/canadian-muslim-rights-group-unveils-61-ways-to-fight-islamophobia-48522

PCVE Program of the NCMF North Luzon

The National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) North Luzon spearheaded a 2-day program on preventing and countering violent extremism (PCVE) on May 24 and 25, 2021 in Baguio City. The theme of the program is “Bridging the Roles of Government and Islamic Institutions in Countering Violent Extremism”.

The 2-day activity was led by NCMF Commissioner Saidamen Balt Pangarungan and the father-daughter tandem NCMF Administrative Services Director Abel Macarimpas and NCMF North Luzon Regional Director Raihanah Sarah Macarimpas.

The last day of the program was graced by the Mayor of Baguio City, Honorable Benjamin Magalong graced and supported the activity of the NCMF. Also present during the closing ceremonies were Honorable Ley Llyoyd Braza Orcales, Attorney Ferdie Guro, and PB Naseef Joel Omar.

Mustaqim supports all the programs of the NCMF on PCVE and encourage all other NCMF offices to replicate said activity as this is vital in bringing together a whole-of-nation approach in addressing violent extremism and ensuring peace and stability in our nation.

Peacebuilding Training For Zamboanga Youth Leaders

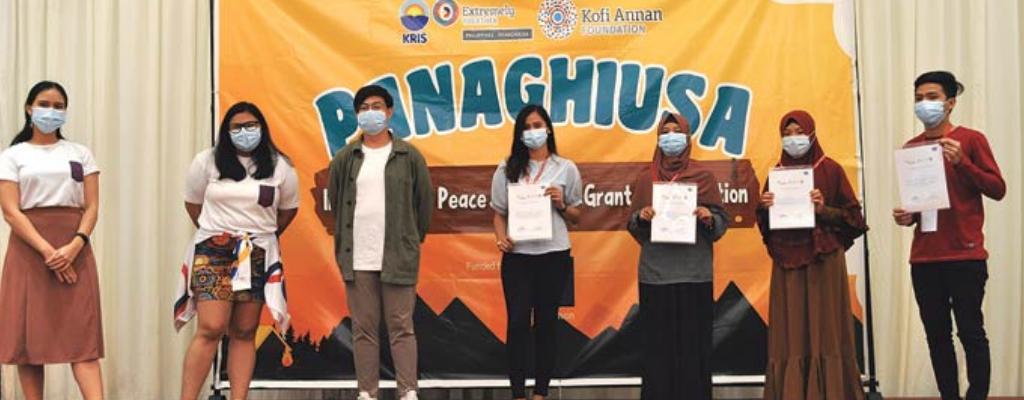

The Manila Times reported on April 19, 2021 that over 200 youth leaders took part in a peacebuilding training in Zamboanga City on March 14 and 17. This training was formed under the Extremely Together (ET) Philippines-Panaghiusa program funded by the European Union (EU) and led by the Kofi Annan Foundation (KAF) and Philippines-based non-profit organization KRIS.

Said training imparted to the youth leaders valuable lessons on the history of violent extremism in the Philippines; preventing violent extremism; developing solutions towards peace, and conceptualizing and managing projects under the initiative.

Ymari Pascua, the Project Lead of ET Philippines shared “Taking inspiration from the former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan who believed in the power of young people and who started the Extremely Together movement, we trained these youth from Zamboanga, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi and Basilan so they can work together and take the lead in promoting peace.”

Following the sessions, the youth groups presented their proposals for promoting peace in their own communities, with six groups selected during the two events slated to receive P30,000 each as a seed grant.

We at Mustaqim are proud of all the efforts and achievements of our youth leaders in achieving peace in our country!